Congolese Prime Minister Matata Ponyo is famously bullish about the economy: ““If we do 7.7 percent this year, what will prevent us doing 9 percent next year?”

The answer, it turns out, is the world economic slump. And it comes at the worst possible time for the ruling government, which is embroiled in a battle for its survival. But before we get there, some context.

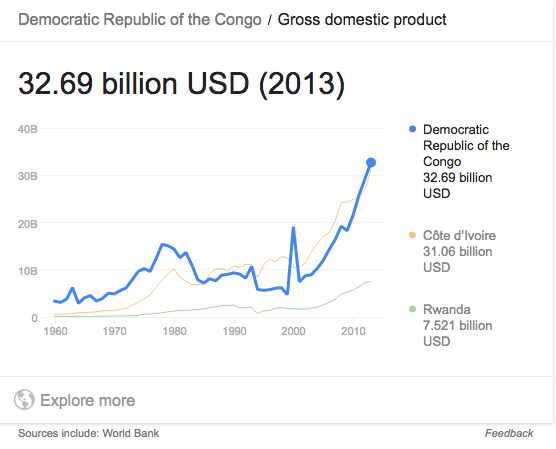

There are few accolades that the Congo has earned in recent years. Most news about the country deals with the violence in the East, or the trouble-ridden electoral process. However in one area, the government has reached for superlatives: the economy. Buoyed by a sharp rise in copper exports, the country has seen its GDP rise exponentially in recent years. Copper exports quadrupled between 2008 and 2014, when the country exported over 1 million tons; the GDP followed suit.

The Congo is still one of the poorest countries in the world and, while data is poor, it does not appear that the growth has put much of a dent in poverty rates (it has declined from 71 to 63 percent between 2005 and 2012). Nonetheless, “Monsieur Cadre Macroeconomique,” as people like to call the prime minister, has been able to keep inflation close to zero and growth rates among the top ten in the world.

That is, until the commodity slump of late last year. In late 2010, world copper prices were at around $10,000 per metric ton; by this year, they were less than half that. Oil prices have gone from $120/barrel to $40/barrel in a similar time frame. Together, oil and copper use to make up around 20-25 percent of the country’s revenues.

The impact on the economy has been dramatic. Last year, the government ran a $200 million budget deficit, roughly 3% of its revenues. In the United States that would be considered superb. The Congo, however, is hard pressed to find major creditors, and has to address deficits by printing money, slashing spending, and simply going into arrears on its debt. It has apparently done a mixture of all three, leading to moderate inflation––the franc, which has been stable for years, has depreciated from around 900 to around 965 per US dollar. It has delved into its foreign currency reserves, depleting them to around 6 weeks of imports. And the crisis shows no sign of abating––the global commodity slump is unlikely to improve as long as Chinese growth flags and the rest of the world economy (with exceptions like India and the United States) putters along in first gear.

Why is this important for Congolese politics? For several reasons. If inflation does rise considerably, it will hit consumers hard, eroding the little purchasing power the average Congolese have, making them more amenable to riots and protests. For the many urban dwellers who live hand-to-mouth, this can be the difference between eating once and twice a day. Ironically for Matata, who has been pushing against the dollarization of the economy, the fact that over 80% of the economy still trade in American currency should provide a firewall.

Secondly, the Congolese are already looking for foreign help in bailing them out. According to western donors, they have already begun asking around in embassies and among international financial institutions. The International Monetary Fund, however––the most logical source of a bailout––has suspended its program in the Congo since 2012 due to governance problems. One diplomat told me that the economic squeeze could increase donor leverage during the electoral process. “The response will be: we can lend you money, but it will be conditional on political reforms and guarantees for the elections.”

We are still some ways away from that day. For now, the government has announced that they will be cutting salaries for senior officials––minister, parliamentarians, and managers of parastatals, by 30 percent. it has also been able to to lure Chinese investors with low copper prices––Chinese companies have pledged $1,5 billion in investments in recent months. Sooner or later, however, the government will have to consider more radical steps.