Thijs Van Laer is Program Director, Prevention and Resolution of Displacement, with International Refugee Rights Initiative (IRRI) in Uganda.

In December 2018, only two weeks before national elections, hundreds of people were killed in a massacre in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This time, the grim scenes did not play out in the east, where armed violence has marked people’s lives for decades, but in western Congo, 300 km northeast of the capital Kinshasa.

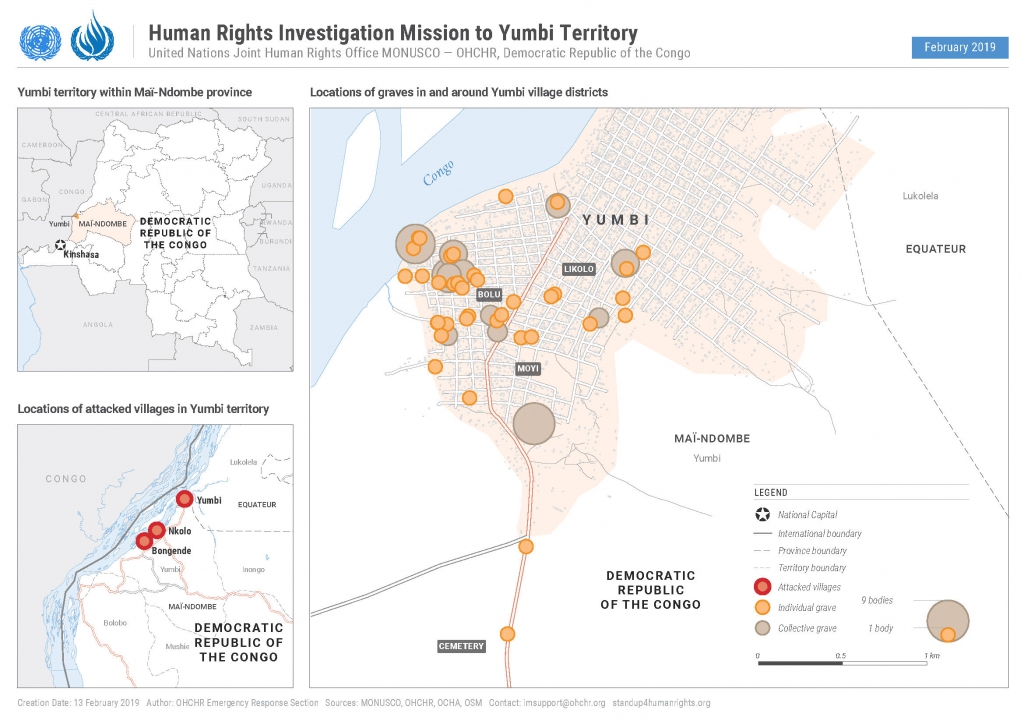

According to the UN, more than 535 people were killed in Yumbi (Maï-Ndombe province) during attacks that were organized and planned by members of the Tende community against members of the Nunu community, which lasted less than 48 hours. 16,000 people fled to neighboring Congo-Brazzaville, and more than 12,000 sought refuge on islands in the Congo River or in nearby towns.

Yumbi was not on the radar of actors working on conflict in the Congo, as was the case for recent episodes of violence in the Kasai region and Ituri and Tanganyika provinces. In order to understand what causes these conflicts and displacement, International Refugee Rights Initiative (IRRI) conducted its own investigations in Yumbi, interviewing 35 victims and other people knowledgeable about the events.

Background

The immediate event that sparked the attacks was the burial of a deceased Nunu customary leader in Yumbi town, on the night of December 14th. Members of the Tende community had warned the Nunu not to bury their chief in the town center, and the authorities had forbidden it, but the Nunu went ahead and put their leader to rest next to his predecessors, as demanded by custom. After doing so, they went out on the streets to celebrate their success, chanting songs that were seen as a provocation by the Tende and allegedly attacking houses occupied by citizens of Tende ethnicity.

In Yumbi town, the Tende are a minority, but in the whole territory of the same name, they outnumber the Nunu. For decades, the two groups have been competing over access to land, power and other resources. The majority Tende claim that the land is theirs and occupy most of the customary and administrative positions on the local and provincial level. This has fueled frustration among the minority Nunu, who are seen as relatively better off, including because of their fishing activities. The Nunu have regularly pushed for the creation of their own administrative entities, led by their own customary leaders, which would give them greater influence, in particular regarding land. These attempts have led to confrontations with other communities, including the Sengele in Nkuboko village (Inongo territory) in November 2018, and with the Tende.

There are historical antecedents for this violence, as well, with clashes taking place in 1963, 2006 and in 2011. Both groups also resorted to alliances with powerful outsiders too: the Nunu were allegedly favored by Belgian colonizers, while the Tende benefitted when Laurent-Désiré Kabila came to power. Each of these episodes reinforced resentments on both sides planted the seeds for the next clashes.

The December events

Following the burial ceremony, Tende mobilized in nearby villages. They attacked Yumbi on December 16th and nearby Bongende and Nkolo-Yoka on December 17th. Interviews conducted by IRRI with survivors confirmed the organized and brutal manner in which the attacks were carried out. Given the speed of the mobilization, victims and observers suspect that the perpetrators were enacting a preconceived plan.

Tende fighters came in large numbers, from several directions, armed with machetes, hunting guns but also military weapons and amulets. They went from house to house, killing residents, looting property and setting houses on fire. Some manned roadblocks to prevent Nunu from escaping, or attempted to kill those who fled on canoes on the river. Survivors recounted how family members were burned alive or dismembered. A witness said she heard men in military uniform say: “Our mission is to kill the Nunu. If we shoot at them and they are not dead yet, you have to finish them off with machetes.” Criminal proceedings would we need to decide whether crimes against humanity or even genocide was committed during the attacks.

Some Nunu attempted to put up resistance and conducted reprisal attacks – IRRI interviewed a Tende who said Nunu killed several of his family members in Yumbi – but they were outnumbered, ill-prepared and less equipped than the attackers. Witnesses told IRRI they saw police officers participating in the attacks on the side of the Tende, as well as individuals in military fatigues. These could have been demobilized soldiers, or active military participating on their own behalf. The militia attacked a position of the naval forces, killing at least one of its members in Bongende; but was overall faced with little resistance from state security forces.

Response

After a few days, military and police reinforcements arrived and restored a fragile order. Many people we spoke to advocated for reinforcing the state presence and sharply criticized provincial authorities for their late and limited reaction to the events, even though they were aware of what was happening. Residents refused to accept a civilian administrator sent from Inongo, the provincial capital, to replace his killed predecessor, and preferred to keep the interim military administrator in place. Many blame the outgoing governor, Gentiny Ngobila, himself a Tende, as well as a Tende customary leader and a police commander of being behind the attacks, but IRRI has not seen any conclusive proof that this was the case. Ngobila has since been elected governor of Kinshasa.

The UN peacekeeping mission (MONUSCO) sent peacekeepers to secure the area and conducted a thorough human rights investigation into the events. However, much as with the violence that erupted in the Kasai region in late 2016, the mission has struggled to respond to such events––its reduced presence in western DR Congo and its many competing challenges have contributed to this.

One of the objectives of the reinforced security presence is to allow for refugees in Makotimpoko (Congo-Brazzaville) or displaced people inside the country, to return. Military and civilian authorities have urged, or even pressured people to do so. A significant number has heeded such calls, but others remain skeptical because of the worrisome security and living conditions. Many displaced people do not even have a house to return to, and may have to confront the perpetrators upon return and relive their trauma. More humanitarian actors are now arriving in the area, but the needs are immense, as more than 1000 houses, 14 schools and 4 health centers have been destroyed.

Elections

Invoking the security situation, the electoral commission CENI decided on 26 December to postpone the provincial and national legislative elections in Yumbi, as it did in parts of North-Kivu province. Its office in Yumbi had been burned down in the attacks. Despite many concerns that displaced people, mostly of Nunu ethnicity, would not be able to vote, elections finally took place on 31 March. The party of former president Joseph Kabila, the PPRD, won the two seats at stake in the provincial and national assembly.

Both candidates hail from the Tende community, which is seen to be closer to Kabila than the more opposition-leaning Nunu. The latter are likely to contest the result, as they already feel underrepresented on all levels. Given the timing of the attacks, many of course suspect a link with the electoral process, as was the case for previous violence in the 2006 and 2011 election years.

Local elections could constitute the next flashpoint, currently scheduled for September. While they could allow for more inclusion and local accountability, there are serious risks that electoral competition amidst many fault lines over identity, power and resources could again result in violence, in Yumbi and elsewhere, particularly if elections are manipulated and disputes are badly handled.

Reconciliation and accountability

The risks of renewed violence will remain high if efforts to promote reconciliation and accountability remain neglected, as they currently are. Some steps are being taken in this direction: A government delegation has visited the area to promote reconciliation, and leaders of the two communities have been invited to Kinshasa for a dialogue. Twenty-one suspects have been arrested and transferred to Kinshasa. Witnesses, however, mentioned names of several other perpetrators who remain at large.

A Catholic nun told IRRI: “We need reconciliation. But people also need justice, real justice. If not, there will never be reconciliation.” Hasty returns of displaced people, inappropriate responses by the security forces and unaddressed traumas could reignite the conflict, despite many stories of previous co-habitation and solidarity during the violence, among ethnic divides. To avoid renewed conflict, it is crucial to invest heavily in reconciliation efforts and extend UN investigations and prosecutions to those who organized the violence.