A week ago, UN peacekeepers struck a deal with the Congolese government to restart joint operations against the Rwandan FDLR rebels. It seemed to be a victory for the UN, whose efficiency in the East has been hampered by poor relations with its Congolese counterparts. Military collaboration had ceased since January 2015, when a row broke out over two Congolese army generals the UN said were guilty of human rights abuses.

That deal seemed to be almost immediately in jeopardy when the head of UN peacekeeping, Hervé Ladsous, said on Radio France International that one of the two generals was now being charged and another had been redeployed. Not true, the Congolese information minister replied, saying that no one had been tried and that one of the two generals was still in the same position.

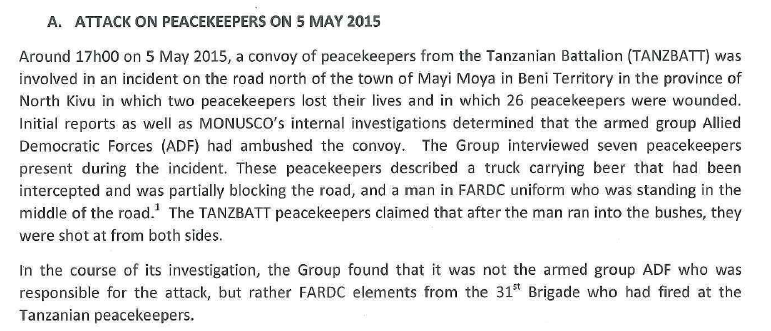

But should the UN have been trying so hard to restart collaboration in the first place? This question was starkly framed when, almost at the same time, a letter leaked from the UN Group of Experts on the DR Congo to the Security Council. In the letter, the Group concluded that the same army with which the UN was eager to resume collaboration may have been guilty of killing its peacekeepers. The leaked memo says:

As one can see, the Group disagrees with MONUSCO, which did conduct its own investigation and found the ADF to have been responsible. But research conducted by the Congo Research Group, which is based on eyewitness testimony and will soon be published, confirms this part of the Group’s conclusion. We also find that the UN has been quick to call attribute most of the disparate kinds of violence around Beni––where around 500 people have been killed since October 2014––to the ADF. In his interview, Ladsous went so far to state that the ADF has « confirmed links to Al-Shabab, » even neither the UN Group of Experts or our researchers have been able to confirm these links. Indeed, violence around Beni seems to have been perpetrated by various forces, and has benefitted from the complicity of certain members of the FARDC.

The report also suggests that the Congolese army may have attacked the UN peacekeepers because they suspected them of selling weapons to the ADF. Other sources report that peacekeepers came across the Congolese soldiers while they were looting a beer truck, provoking a shoot-out.

Ever since the UN began collaborating militarily with the Congolese army a decade ago, the joint operations have been mired in controversy. Since the 2003-2006 transition, the peacekeepers have largely ceased to be mediators and political brokers, and have increasingly supported the Congolese army as part of its mandate to « extend state authority. » This has, on the one hand, given them the ability to work from within the 130,000-strong army to promote greater accountability and discipline. On some occasions, for example, during the M23 crisis, this collaboration also enabled the Congolese government to get rid of armed groups that were threatening national stability.

But the UN’s backing of the Congolese army has meant that it has become a party to the conflict. During its collaboration with the Congolese army in 2009, international NGOs became wary of having anything to do with MONUSCO, even going so far as refuse security escorts, and the International Committee of the Red Cross began treating MONUSCO demobilization camps as prisons and inspecting them.

The UN has put in place measures to mitigate the risks inherent in this collaboration, by implementing a « conditionality policy » in 2009 that reviews the human rights records of commanders it is collaborating with (it was that policy that raised a red flag over the two aforementioned generals), and setting up a profiling team to write up in-depth profiles of notorious abusers and spoilers. It has also pushed for, on several occasions, the vetting of Congolese army officers during the process of security sector reform.

The main question that is once again thrown into relief by the leaked report is: Is UN backing of the Congolese army in the interest of the Congolese people and of the United Nations? Has it given the UN privileged access into and leverage over the Congolese army, or just made blue helmets complicit in human rights abuses?