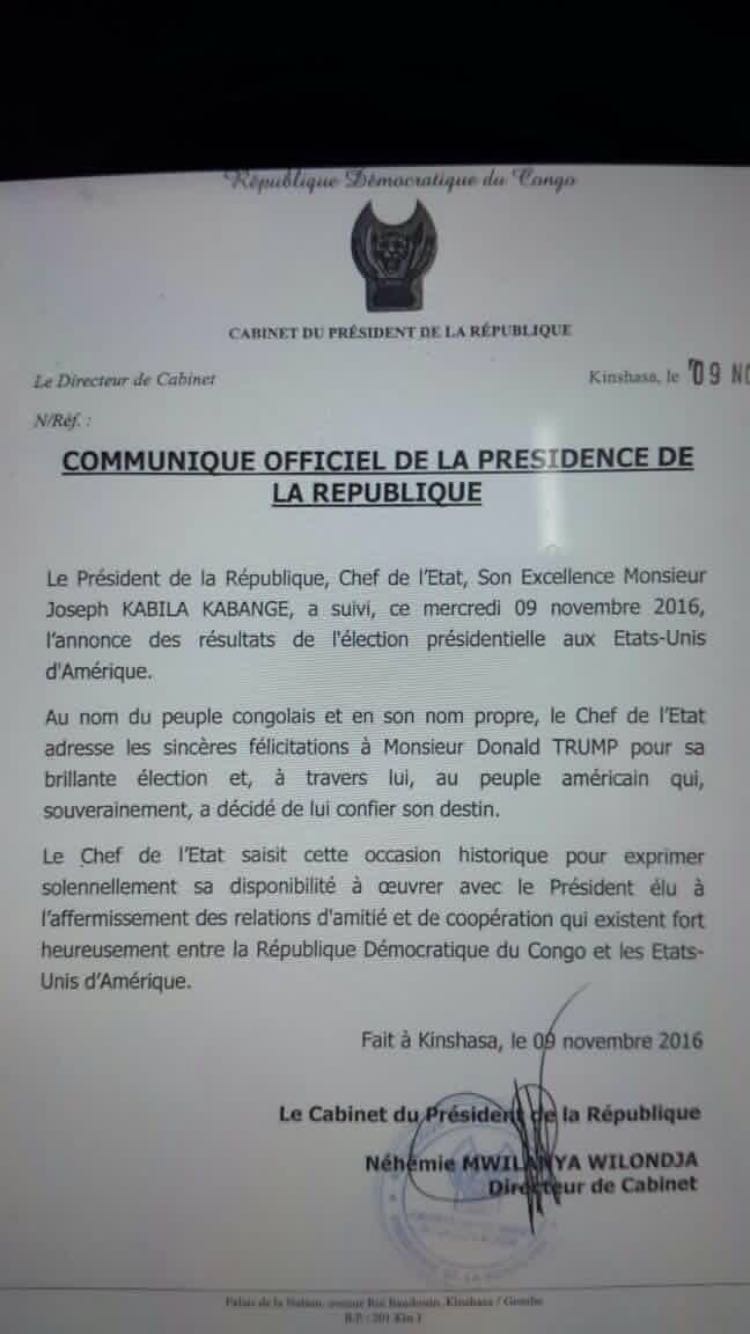

The Kabila administration is not known for quick reactions––it can take them days or even weeks to react publicly to massacres in the eastern Congo, for example.This morning, however, just hours after Trump made his victory speech, President Kabila wrote to congratulate him on « his brilliant election. »

What will the consequence of Trump’s election be for the Congo? Is Kabila right to celebrate?

Yes, he is. While there has been bipartisan support in the US Congress for playing hardball with the Congolese government, there is no doubt that the impetus has come from the Obama administration, and from the Office of the Special Envoy to the Great Lakes, in particular. That office will shut down in around six weeks, and it is highly unlikely that a Trump administration will keep the office open. There will probably be a rush now to push through more sanctions against Congolese officials––Kalev Mutond (head of civilian intelligence) and Evariste Boshab (minister of interior) would be the highest-ranking targets they could go after.

To be clear: it is not that Donald Trump would be a great friend to President Kabila. It is simply that a Trump administration is unlikely to (a) think the Congo (or Africa, for that matter) is much of a priority; and (b) they will be hard-pressed to find people who know much about the continent. Many academic and policy-wonks who deal with Africa are Democrats, and many of the Republican ones repudiated Trump (e.g. Jendayi Frazier, Chester Crocker). This will give Kabila space to maneuver.

What does a Trump presidency mean for Africa in general?

- Potential economic decline. If Trump really does impose a 45% tariff on imports from China, it will further slow down growth in that economy, which is likely to accentuate the slump in the world’s commodity markets. That will adversely affect the commodity-dependent African economies (Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Sudan, South Sudan, Chad, Zambia, Congo-Brazza––and yes, DR Congo).

- Decline in aid. Like so many areas of policy, we really have no idea what Trump will do with the foreign aid budget. Looking at some of the people likely to get jobs in foreign policy, we might see a decrease in aid, funding for the United Nations, and an end to the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and the Electrify Africa Act. Newt Gingrich, who has been mentioned as a possible Secretary of State, has said: « After several years of looking at the UN, I can report to you that it is sufficiently corrupt and sufficiently inefficient. That no reasonable person would put faith in it. » John Bolton, another Trump ally, has famously said the UN could do without its ten top floors. [Fun fact: Gingrich wrote his PhD on Belgian educational policy in the Congo]

- Continued militarization. Trump is not a humanitarian interventionist, but he has said he will « bomb the shit out of ISIS. » So he would be likely to continue supporting counterterrorism operations in the Sahel and Somalia. On the flipside, given his admiration for Putin’s Russia, it is difficult to imagine much staunch support for democracy on the continent.

Some have argued that this might be good for the continent, as a more isolationist America will force these countries to path their own ways. I find it hard to be so sanguine. First, as I state above, I don’t think the US with withdraw, it will just be influenced more by realpolitik and less by lofty ideals. And I don’t think an aggressive push for private investment––without greater transparency and scrutiny of fiscal paradises––and greater military involvement in Africa is the way to go. Let alone more sinister policies––after all, Paul Manafort, who was Trump’s campaign chairman for several months, was a lobbyist for Mobutu and Savimbi in the 1980s. Secondly, a decline in support to the UN and the AU will undermine much-needed multilateral diplomacy and peace-building on the continent. Lastly, while I fully agree that countries need to chart their own paths, in some cases the United States can play a critical role staving off crises and opening up space that can allow that to happen. The Congo is currently a case in point: an authoritarian drift could erode the gains the country has made over the past decade and preclude any genuine domestic dialogue and solution.