By CHRISTOPH VOGEL

On the afternoon of 15 September 2017, the Congolese border town Kamanyola witnessed the deadliest massacre in South Kivu’s Ruzizi Plains since 2014’s Mutarule carnage. At least 36 Burundian refugees and two Congolese (a soldier and a policeman) were killed in what seemed a spontaneous outbreak of violence, just a few hundred meters away from a nearby UN base. Almost two weeks later much remains unclear. So, what do we know about the incident?

Since Pierre Nkurunziza’s successful attempt to run for a third term in 2015, a concomitant coup attempt by a small cohort of Burundian army officers, and a spate of clashes pitting Burundian security forces against the armed and unarmed opposition, tens of thousands of Burundians have fled to the neighbouring DRC alone. The Lusenda refugee camp, located on the shores of Lake Tanganyika between the cities of Uvira and Baraka, hosts over 30,000 of them. Many more have crossed into DRC in the past two years, often not registered by the Congolese national refugee commission (CNR) or not living in camps like Lusenda which are run by CNR and the UNHCR.

At the same time as the arrival of Burundian refugees in mid-2015, Uvira and Fizi territories witnessed a new wave of Burundian armed mobilization as armed groups set up rear-bases in eastern DRC. An organization called RED-Tabara– close to opposition politician Alexis Sinduhije – tried to get a foothold in the Ruzizi Plains and the Moyen Plateaux. Following a damning UN report in mid-2016, however, it became difficult for RED-Tabarato maintain its level of outside support and the group weakened after various clashes with local Congolese militias. From then it was another armed branch of the Burundian opposition that became more important –FOREBU, now known as FPB. As opposed to Tabara, FOREBU has been around from the early stages of the turmoil around Nkurunziza’s third-term bid, but it did not seek to establish foreign rear-bases as quickly as Tabara. First led by putschist general Godefroid Niyombare, it later split and developed a DRC-based branch under the leadership of other Burundian army defectors. Like the FNL armed group has done for many years, both of these more recent Burundian groups are reported to have entertained short-lived alliances with local Congolese armed groups in Uvira and Fizi territories.

The existence of armed Burundian opposition on DRC soil appears to have pushed Burundian security services to intensify incursions into DRC territory and cross-border collaboration with the Congolese army (FARDC), and potentially to have engaged in weapon supply for Congolese armed groups suspected to be hostile to Bujumbura’s foes. While cross-border collaboration has been fairly harmonious, it has in at least one case led to fighting between the two national armies. In late December 2016, Burundian soldiers opened fire on the FARDC, who they might have believed were FNL-Nzabampema combatants or other Burundian rebels. Overall, though, the tight collaboration between the two governments together with the climate of suspicion, has led refugees, cross-border traders, and day laborers to be considered as potentials rebels. Accounts of forcibly repatriated Burundians, alongside instances of mistreatment, have made the news within Burundian refugee communities and amplified pre-existing fears.

What does this have to do with Kamanyola? A bustling border town and historical site (in 1964, the Zairian army landed a key victory against the Mulelist insurgency here), Kamanyola is a place of tension and friction but also, by its mere geography, of social encounters and economic exchange. Since late 2015, followers of a religious sect led by ‘Euzebia’ or ‘Yezebia’ had arrived in several waves, with latecomers joining earlier arrivals. Most of the roughly 2000-3000 acolytes refused being registered and claimed they had fled Burundi for having been associated to opposition party FRODEBU (the party of murdered president Melchior Ndadaye, whose current leadership mostly lives in exile as well) and that any CNR registration would lead to cantonment in Lusenda or elsewhere and subsequent exposure to hidden reprisals by the Burundian army or Imbonerakure squads.

Recently, this community began to run their own evening and night patrols – further increasing the suspicion of Congolese authorities (who just in March 2017 had detained two dozen alleged associates of a militia hiding in a local house) in Kamanyola. On 12 or 13 September – accounts differ on the date – four Burundians were detained by police and brought to the Congolese intelligence (ANR) for performing such nightly patrols brandishing clubs (no guns were displayed). In a video of their interrogation, they said they had arrived from Burundi within the last 5-6 months.

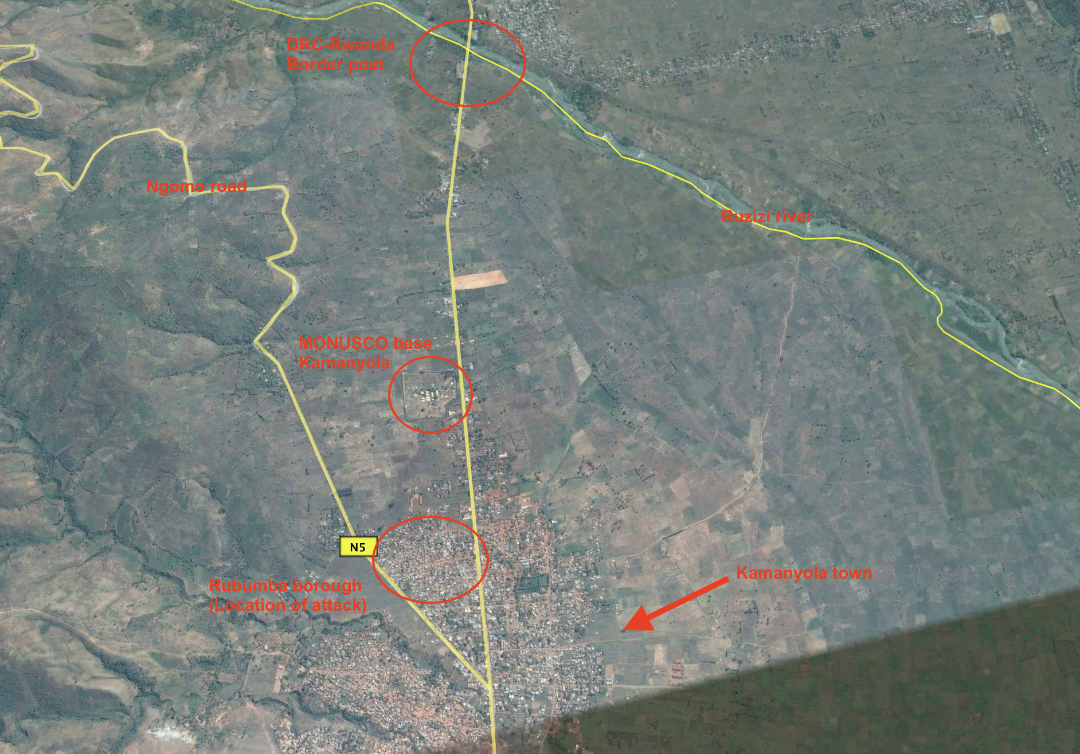

Fearing these four would be forcefully repatriated, members of their community went to demonstrate on 15 September and, from around 11am, gathered in the Rubumba neighborhood, close to the office of the national intelligence agency. According to South Kivu civil society, local authorities had decided to send them to UNHCR in Uvira – which many Burundians believe leads to forceful repatriation. Eyewitnesses reported that the situation escalated from around 330pm, when demonstrators became impatient and began throwing stones while demanding the release of the fellow Burundians.

The modest number of Congolese policemen and soldiers was unable to control the crowd; eventually demonstrators managed to overwhelm one soldier (some witnesses say a policeman), steal his weapon and begin shooting. At this point – around 4pm – Congolese security forces riposted with live fire – somes eyewitnesses spoke of a sub-machine gun – into the crowd and were subsequently reinforced by additional FARDC troops. At least 36 Burundians, one FARDC and one PNC element were reported dead after the clash. Immediately after the carnage, rumors spread about an alleged participation of Imbonerakure – the Burundian ruling party CNDD-FDD’s youth wing – in FARDC uniforms, but these were never substantiated. Additional sources reported cross-border movements of Burundian soldiers near Uvira, but this is also speculative.

The nearby MONUSCO base – situated between 300 and 400 meters away from the carnage – reacted only after 5pm, with the UN communiqués later stating the shooting had not begun long before that time (a claim contradicted by all other sources). However, not all of the victims seem to have been killed in the shooting: Even before 15 September, a systematic pattern of intimidation of the Burundians in Kamanyola was reported, including public threats by local and customary authorities – likely motivated by that fact that some of Burundians had settled on ancestral land of the Shi community near the center of Kamanyola. Subsequent anti-Burundian rabble-rousing repeatedly led to pillages and the stoning of at least 3-4 Burundians earlier in the morning of 15 September – a situation some observers claim was orchestrated by outside actors were considered the refugees as a security threat to the current Burundian government.

Over two weeks after the killings, the situation remains tense around Kamanyola, and many Burundians have regrouped near the MONUSCO base in hope of protection. As of yet, however, no durable solution to the problem has been found.

Christoph Vogel is a doctoral student at the University of Zurich. This article was also posted on https://suluhu.org/.